World’s first wooden satellite, developed in Japan, heads to space

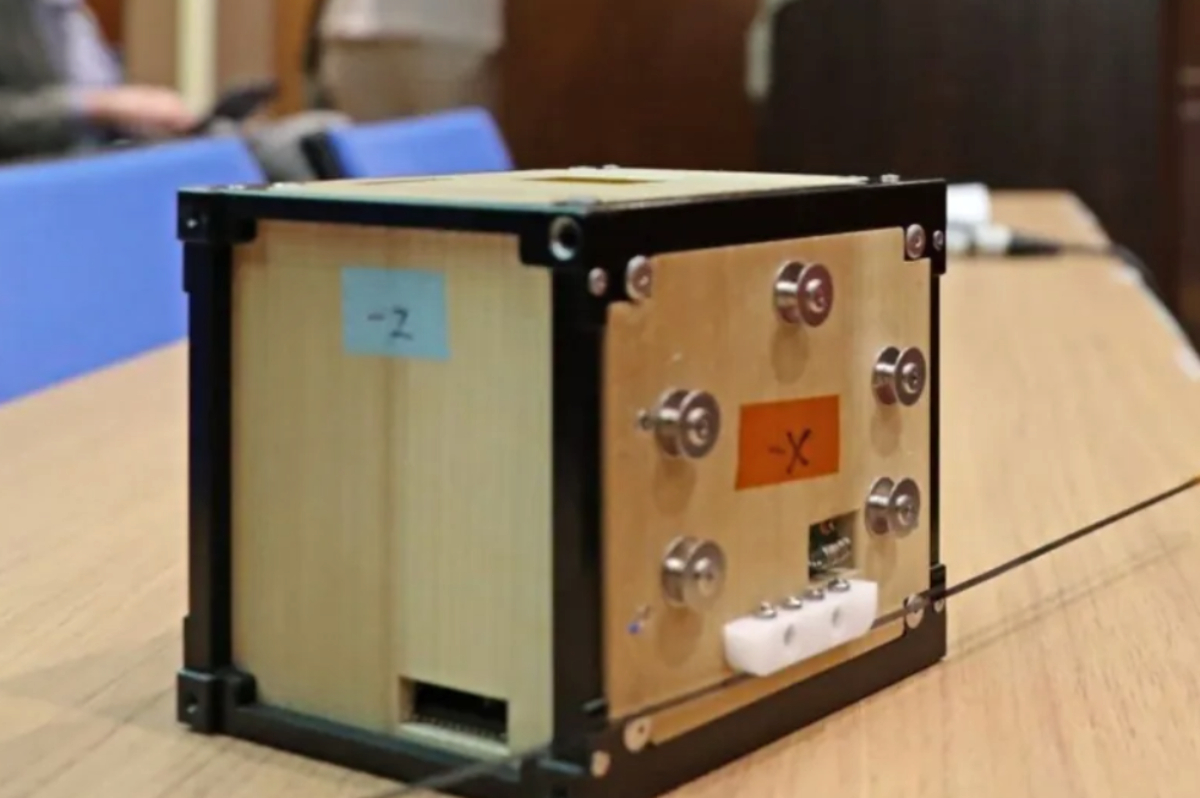

The world’s first wooden satellite, LignoSat, developed by Japanese researchers, was launched into space on Tuesday, marking a groundbreaking step in testing timber for future lunar and Mars exploration. Created through a collaboration between Kyoto University and Sumitomo Forestry, the palm-sized satellite was sent to the International Space Station (ISS) aboard a SpaceX mission. It will later be released into orbit, approximately 400 kilometers (250 miles) above Earth.

Named after the Latin word for “wood,” LignoSat aims to showcase the potential of renewable materials for space exploration. “With timber, a material we can produce ourselves, we could build homes, live, and work in space indefinitely,” said Takao Doi, a former astronaut and professor at Kyoto University who studies human activities in space.

The project is part of an ambitious 50-year plan to plant trees and build timber-based structures on the moon and Mars. Doi’s team developed the NASA-certified wooden satellite to prove that wood can withstand the challenges of space. “Early airplanes were made of wood,” noted Kyoto University forest science professor Koji Murata. “A wooden satellite should be feasible too.”

Wood offers unique advantages in space. Unlike on Earth, where oxygen and water cause wood to degrade, the vacuum of space prevents rot and combustion, enhancing its durability. Additionally, wooden satellites pose less environmental risk when decommissioned. Unlike metal satellites that release harmful aluminum oxide during atmospheric re-entry, wooden satellites simply burn up with minimal pollution. “Metal satellites might eventually be banned,” Doi speculated. “If LignoSat proves successful, we plan to pitch it to SpaceX.”

The research team identified honoki, a type of magnolia tree traditionally used in Japan for sword sheaths, as the ideal material for spacecraft. After a 10-month experiment aboard the ISS, honoki demonstrated its resilience in extreme conditions. Using traditional Japanese craftsmanship, LignoSat was constructed without screws or glue.

Once deployed, LignoSat will remain in orbit for six months, where its onboard electronics will monitor how the wood withstands the harsh conditions of space. Temperatures in orbit shift drastically, fluctuating between -100°C and 100°C (-148°F to 212°F) every 45 minutes as the satellite transitions between sunlight and darkness. The satellite will also assess wood’s ability to shield semiconductors from space radiation, potentially opening doors for applications like building data centers in space.

“This might seem like a step back in time, but wood is at the forefront of technology as we look to the moon and Mars,” said Kenji Kariya of Sumitomo Forestry Tsukuba Research Institute. He emphasized that using wood in space exploration could breathe new life into the timber industry, making it a cutting-edge material for a new era of innovation.